With some 45,000 students in a population of just over 200,000, it’s not surprising Graz punches way above its weight when it comes to the visual arts. In our short time there, we toured two major galleries and looked in at a private gallery on the main square of the old town.

Guaranteed to turn critics of the Art Gallery of Ontario apoplectic, Graz's Kunsthaus offers good exhibition space for avant-garde art.

We started with the Kunsthaus, a structure built in the shape of a cross between a human heart and the bag part of bagpipes. People who hate the new facade of the Art Gallery of Ontario would be appalled. We paid our eight-Euro admission (each) and were advised that for 11, we could buy a day pass. Thinking we wouldn’t have time to get the full value from the pass, since it was mid-afternoon, we paid the single admission price. But the attendant told us we had 24 hours in which our ticket acted as a discount, so that we never had to pay more than three more Euros to see all the museums we could manage until the ticket expired. We saw two galleries and a museum, all of which were worth the time.

The Kunsthaus is built on several huge, open levels, ideal for the kind of installations we saw. On the lower floor, there was an exhibition of avant-garde Austrian photography; interesting but somewhat incomprehensible. Entering what seemed to be the permanent collection, we were treated to a number of works which might be described as very industrial. Loud clangs emitted from powerful speakers, giving the feeling that the entire exhibit was derivative of the movie Eraserhead. It seemed like something you’d expect see in the heart of industrial Germany rather than what seemed to be a fairly rural part of Austria. Nevertheless, in my constant search for Eraserhead moments the world over, this was certainly one that qualified.

Help for white people

In the upper level, where the building’s giant heart valves/pipe sockets acted as skylights, was an exhibition of installations by an artist who had recently spent some time in Bénin, one of the poorest countries in Africa. There was a pile of huge jerry cans and old bicycles, supplemented by video of people riding all kinds of two-wheeled contraptions with unlikely stacks of 50-litre cans. Were they carrying water or fuel? Another installation cleverly depicted the devastation of the beach: a panel of a crashing wave set in front of a sand “beach,” littered with flat metal sculptures of dead fish.

But the highlight was the “NGO headquarters,” a hut the size of a big backyard storage shed, where videos showed NGO employees doing their charitable work in Bénin. Their charity involved collecting money from some of the poorest people in the world to give to white people in the United States. The videos captured their conversations with ordinary folks as they asked for donations clad in their white NGO t-shirts.

Only one man was what mildly hostile to the idea of giving money to white people in the US. Why should we do that when they have taken so much money from our country, he asked. The “NGO employees” answered: since the financial crisis, things have been very hard for a lot of white people in America. And they don’t have families around them. They have to face their problems alone. Here, we are surrounded by love. We are so much better off than them.

Virtually everyone put some money into the plastic tubs which the “employees” carried.

Austrian art traditions

First stop after breakfast next morning was the Neue Galerie Graz. The featured exhibition was a set of installations built around old gym equipment and some dark, depressing paintings and drawings. We quickly skipped through to the permanent collection and an exhaustive exhibition of the works of Wilhelm Thöny, one of Austria’s foremost artistic figures of this century.

The museum, which was in a beautiful converted 18th-century palace, provides an engaging tour of Austrian painting since 1800. The hundreds of older paintings capture rural landscapes and villages; my favorites showed farmers bringing cows home in the rain and the preparations for a village fair.

The museum deals directly with the Nazi years, exhibiting the works of artists who were proscribed by the régime. Many of them, including Thöny, left the country for France and, later, the US.

Austria is not a country that comes to mind when you think about great painters, but the Neue Gallerie gave us both a new appreciation for the artistic tradition and the modern direction of Austrian art.

Art of protest and liberation

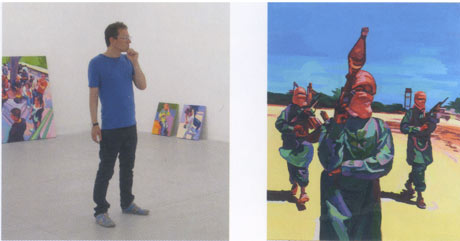

We looked through the windows at several other galleries without stopping in. But after dark,in the cold of the Hauptplatz (main square), we stepped into the Reinisch Contemporary gallery where the works of Anton Petz were on display.

Petz seems to paint people in motion. A scene of a peaceful crowd captures the casual attitudes and poses of people lounging on a set of stairs or in a park; he captures the gestures and attitudes in a style that makes the gathering seem alive. Other paintings are of people engaging in protest or revolutionary acts.

To me, his paintings seem to hearken back to the radical days of the 1960s, where the future was painted in the bright hues of liberation. The colours made the paintings look as if Andy Warhol had painted people instead of soup labels. Petz’s paintings, whether of casual crowds, revolutionaries or refugees, show people coming together, even if just to lounge on a sunny day.

The gallery owners were very polite, answering Ana’s questions and giving us a catalogue and some postcards. We appreciated their hospitality, especially since we didn’t look like we were going to spend €20,000 or more on one of his works.